A Flu by any Other Name

Illnesses we think of as "flu" caused by variety of respiratory pathogens

Respiratory tract infections are one of the most common human diseases. Adults and children can generally be expected to contract between 2-5 and 7-10 of them per year, respectively (Eccles, 2005). The common symptoms of such infections (e.g. sore throat, nasal discharge, coughing, headaches, myalgia, fevers) are easily recognized and, rather than being primarily a function of the virus doing the infecting, are largely influenced by “the age, physiological state, and immunological experience of the host” (Eccles, 2005). When an individual is afflicted with a relatively severe respiratory infection, they commonly describe their condition as “having the flu”. However, a large body of research suggests that respiratory infections in humans result from a multitude of viruses (and sometimes bacteria), some heretofore unidentified, and that influenza is the culprit in only a minority of cases. In fact, over 200 serologically different viruses are known to cause respiratory illnesses in humans and rhinoviruses alone account for 99 serologically unique types (Eccles, 2005; Jacobs et al., 2013).

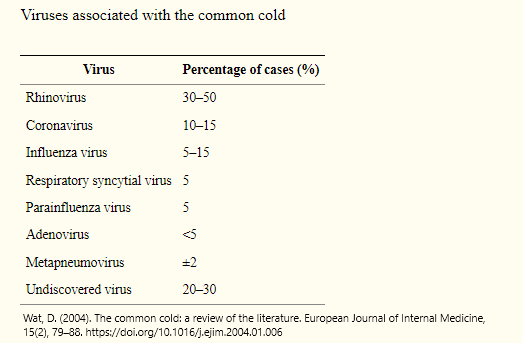

Many studies examining the etiology of patients suffering from respiratory infections have been conducted. For example, a study in Finland examined 200 young adults with cold symptoms over a 10-month period using PCR tests and other methods (Mäkelä et al., 1998). In that study, viral etiology was established in 138 of the test subjects: 105 had rhinoviruses, 17 were infected by coronaviruses, influenza viruses were detected in 12, 14 had infections from other common respiratory viruses, and 7 had bacterial infections. For the remaining 62 ill subjects, no causative viral or bacterial agents could be identified. The authors noted the inability to identify an agent as a common circumstance, with prior research showing that the causative agent goes unidentified in about 50% of respiratory infections. Literature reviews by Wat (2004) and Thomas (2014) also showed similar distributions of viruses associated with respiratory infections.

These findings have also been echoed in more recent studies. In South Africa, researchers examined infections in young children over a 5 year period and found that about 32% patients were infected with RSV, 22% were infected by adenovirus, 15% were infected with rhinovirus, and only 5% were infected with influenza (Famoroti et al., 2018). Another study conducted in the Netherlands (van Beek et al., 2017) found that influenza virus was involved in roughly 18 and 34% of cases of respiratory illness during two seasons, and that numerous other viruses, such as coronaviruses and rhinoviruses were the causative agent in many acute influenza like illness (ILI) cases.

In short, when someone thinks they are suffering from influenza, they are often dealing with another virus altogether. So, given the fact that influenza is the infecting agent in only a minority of cases, how useful are influenza vaccines in preventing this type of illness? Doshi (2013) noted that there have been increasingly aggressive public health campaigns around influenza vaccination, with an ever broadening scope of who is considered “at risk”, and that the number of influenza doses being offered has grown by over 100 million doses since 1990. The CDC claims that “studies have consistently found that the flu vaccine has been effective in reducing the risk of medical visits and hospitalizations associated with flu" (CDC, 2021c). With such marked increases in influenza vaccine uptake, and such strong claims of efficacy, significant reductions in morbidity and mortality due to respiratory illness could be expected. Has this been the case?

Contemporary quadrivalent influenza vaccines are designed to target the four most common circulating influenza viruses (CDC, 2021a) and their efficacy ranges from about 10% to 60% (CDC, 2021b). However, these efficacy numbers become less remarkable in light of the fact that the majority of individuals suffering from influenza-like symptoms are not actually infected by influenza viruses. As previously discussed, the causative agent in the majority of respiratory illness is one of a number of different known (or unknown) viruses, none of which are targeted by influenza vaccines.

A recent Cochrane review (Demicheli, 2018a) of influenza vaccination in healthy adults found that flu vaccines probably reduce influenza from 2.3% without vaccination to 0.9%, and that vaccination might reduce the risk of hospitalization by a mere 0.6%, from 14.7% to 14.1%. The researchers also found that vaccines increased adverse events, with high certainty that vaccine recipients were more likely (2.3%) to experience fever during influenza season than those who did not receive an injection (1.5%). The study included the results from 52 randomized controlled trials, spanning four decades. A similar review, examining influenza vaccination in the elderly, found low certainty evidence that elderly individuals might experience less influenza per season compared to placebo (6% versus 2.4%). The authors of that study wrote: “The available evidence relating to complications is of poor quality, insufficient, or old and provides no clear guidance for public health regarding the safety, efficacy, or effectiveness of influenza vaccines for people aged 65 years or older” (Demicheli, 2018b).

More recently, the authors of a large study in the United Kingdom, including 170 million episodes of care and 7.6 million deaths, wrote: “turning 65 was associated with a statistically and clinically significant increase in rate of seasonal influenza vaccination. However, no evidence indicated that vaccination reduced hospitalizations or mortality among elderly persons. The estimates were precise enough to rule out results from many previous studies" (Anderson et al., 2020).

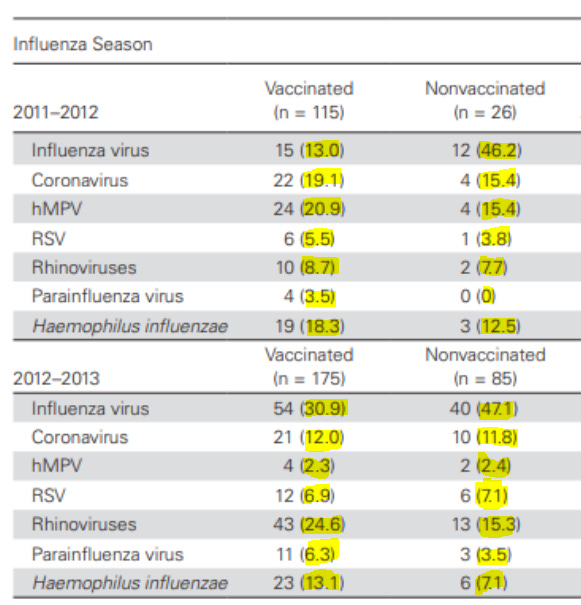

Findings from another study suggested that, while influenza vaccination reduced the number of lab-confirmed influenza cases, it did not reduce the incidence of ILI. In other words, other viruses moved in to fill the gap and infect influenza vaccine recipients (van Beek et al., 2017). Additionally, a similar study showed significantly increased risk of non-influenza respiratory virus infections among those who had undergone influenza vaccination, and the authors suggested that non-specific immunity against other viruses could be affected in recipients (Cowling et al., 2012).

The information discussed above, spanning approximately 100 studies and millions of patients over multiple decades, paints a very different picture than that typically presented by public health officials. So why do public health practitioners seem to be so singularly focused on influenza and influenza vaccination? Are influenza viruses uniquely deadly compared to other respiratory viruses? Research tends to suggest that they are not.

For instance, a study surveying adult hospital admissions with acute respiratory symptoms showed that respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus caused at least as many hospitalizations as influenza, particularly in patients over 65 (Kaye et al., 2006). In another study, patients hospitalized with rhinovirus infections experienced mortality at a higher rate than those infected with influenza (Hung et al., 2017). Similarly, endemic human coronaviruses can cause high rates of mortality. Choi et al. (2021) examined hospital admissions for respiratory illness over a five year period and found that the mortality rate was 25% for patients infected with HCoV-229E and 9.1% for those infected with HCoV-OC43. Coronaviruses can also cause high mortality in care facilities. For example, HCoV-OC43 was the culprit in an outbreak that resulted in an 8.4% mortality rate among the residents (Patrick et al., 2006).

So, given that:

Most respiratory illnesses are not caused by influenza

Many respiratory illnesses are caused by viruses that are not known.

Influenza vaccines do not work well.

In cases where vaccines reduce influenza infections other viruses can take influenza’s place.

Many other respiratory viruses are as dangerous as influenza (or more dangerous).

What is the best approach to protect society from the scourge of respiratory illness? Vaccination? If so, then how many vaccines?

Approaching the problem logically, a vaccination-based approach would require numerous annual injections and would address only a portion of viruses encountered. Would such an approach actually reduce respiratory deaths or would viruses not targeted by the vaccines move in opportunistically? Would this be even more problematic in light of that fact that many of the causative agents of respiratory disease are currently unknown to science? Would offering too many shots be dangerous to patients?

There are many uncertainties, however it seems that a combination of disease prevention and treatment is likely the most feasible path forward for dealing with respiratory illnesses.

References

Anderson, M. L., Dobkin, C., & Gorry, D. (2020). The Effect of Influenza Vaccination for the Elderly on Hospitalization and Mortality. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(7), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-3075

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). “Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine”. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/quadrivalent.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). “CDC Seasonal Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Studies”. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021c). "Flu & People 65 Years and Older". https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/65over.htm

Choi, W.-I., Kim, I. B., Park, S. J., Ha, E.-H., & Lee, C. W. (2021). Comparison of the clinical characteristics and mortality of adults infected with human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 4499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83987-3

Cowling, B. J., Fang, V. J., Nishiura, H., Chan, K.-H., Ng, S., Ip, D. K. M., … Peiris, J. S. M. (2012). Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clinical Infectious Diseases : An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 54(12), 1778–1783. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis307

Demicheli, V., Jefferson, T., Di Pietrantonj, C., Ferroni, E., Thorning, S., Thomas, R. E., & Rivetti, A. (2018). Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004876.pub4

Demicheli, V., Jefferson, T., Ferroni, E., Rivetti, A., & Di Pietrantonj, C. (2018). Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2(2), CD001269–CD001269. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6

Doshi, P. (2013). Influenza: marketing vaccine by marketing disease. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 346, f3037. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3037

Eccles, R. (2005). Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 5(11), 718–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X

Famoroti, T., Sibanda, W., & Ndung’u, T. (2018). Prevalence and seasonality of common viral respiratory pathogens, including Cytomegalovirus in children, between 0-5 years of age in KwaZulu-Natal, an HIV endemic province in South Africa. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1222-8

Hung, I. F. N., Zhang, A. J., To, K. K. W., Chan, J. F. W., Zhu, S. H. S., Zhang, R., … Yuen, K.-Y. (2017). Unexpectedly Higher Morbidity and Mortality of Hospitalized Elderly Patients Associated with Rhinovirus Compared with Influenza Virus Respiratory Tract Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(2), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020259

Jacobs, S. E., Lamson, D. M., St George, K., & Walsh, T. J. (2013). Human rhinoviruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 26(1), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00077-12

Kaye, M., Skidmore, S., Osman, H., Weinbren, M., & Warren, R. (2006). Surveillance of respiratory virus infections in adult hospital admissions using rapid methods. Epidemiology and Infection, 134(4), 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268805005364

Mäkelä, M. J., Puhakka, T., Ruuskanen, O., Leinonen, M., Saikku, P., Kimpimäki, M., … Arstila, P. (1998). Viruses and bacteria in the etiology of the common cold. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 36(2), 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.36.2.539-542.1998

Patrick, D. M., Petric, M., Skowronski, D. M., Guasparini, R., Booth, T. F., Krajden, M., … Brunham, R. C. (2006). An Outbreak of Human Coronavirus OC43 Infection and Serological Cross-reactivity with SARS Coronavirus. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology = Journal Canadien Des Maladies Infectieuses et de La Microbiologie Medicale, 17(6), 330–336. https://doi.org/10.1155/2006/152612

Sonawane, A. A., Shastri, J., & Bavdekar, S. B. (2019). Respiratory Pathogens in Infants Diagnosed with Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Western India Using Multiplex Real Time PCR. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 86(5), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-018-2840-8

Thomas, R. E. (2014). Is influenza-like illness a useful concept and an appropriate test of influenza vaccine effectiveness? Vaccine, 32(19), 2143–2149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.059

van Beek, J., Veenhoven, R. H., Bruin, J. P., van Boxtel, R. A. J., de Lange, M. M. A., Meijer, A., … Luytjes, W. (2017). Influenza-like Illness Incidence Is Not Reduced by Influenza Vaccination in a Cohort of Older Adults, Despite Effectively Reducing Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Virus Infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 216(4), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix268

Wat, D. (2004). The common cold: a review of the literature. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 15(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2004.01.006

Not rocket science by any means but generally speaking with Americans in particular we need complete overhauls of lifestyles from children to geriatrics. Diet and exercise being the largest. And mental health changes.

Poisoned cell (virus) = dis-ease.

Processed foods, city water, geoengineering, cleaning products, all Rx drugs, vaccines, etc contain toxins and poisons. This is why we get "sick". Symptoms are a sign of the body purging these poisons/toxins.